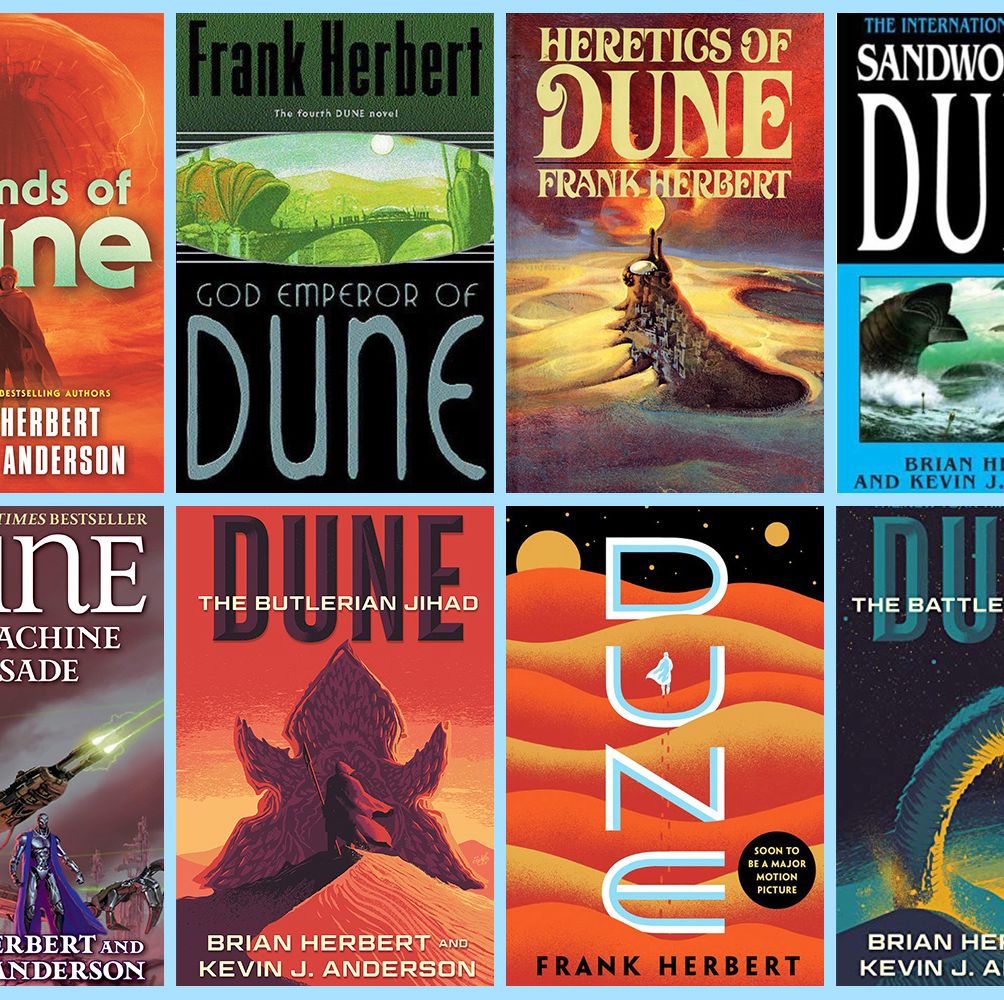

| Elaine Byrd wanted a second child. The longing began after a hectic period in 2015, when she'd cared for three children under the age of two: her daughter, Ember, and a relative's infant twins. Fortunately, Elaine, a kindergarten teacher in the suburbs of Memphis, liked babies. Years earlier, she'd fostered several children. At least with infants, there were no midnight calls from the police, no fights in the street. Instead, there were court dates, doctor appointments, paperwork. Elaine needed more help than Ember's father was willing to give, and after they'd had the twins for a couple months, she left him. Caring for the children was easier on her own, which didn't mean it was easy. One day she drove by a church whose lawn was studded with crosses representing the souls of aborted fetuses. She called the pastor. "In my house there are a couple of babies that could've been aborted," she told him. "Now they're here, and I have to go to work." The next morning at 6:30 sharp, a lady from the church showed up to watch them, and she came back every day after that. Bob Kadlec was standing in his Washington, D.C., office holding a dry-erase marker, the words Manhattan Project scribbled across the top of a whiteboard. Kadlec, who was known on Capitol Hill as Dr. Bob, was the former Air Force doctor and intelligence officer who ran an obscure division of the nation's health department called the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response. It was the afternoon of Friday, April 10, 2020, and Kadlec was surrounded by four of his most trusted associates—and a very large stack of pizza boxes. The novel coronavirus had overwhelmed hospitals in New York City to such a degree that the dead were piling up in refrigerated trailers in the parking lots. Recognizing that the country couldn't shut down forever, Kadlec's crew had assembled for a brainstorming session here inside the Hubert H. Humphrey Building, a blocky, eight-story structure that houses the Department of Health and Human Services. At exactly 5:00 p.m., Peter Marks would be calling. A lanky man with tortoiseshell glasses, Marks was the director of the FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, the referee who would make or break the fortunes of vaccine companies. It was a slow day until apprentice Ian Fox spotted a smoke a quarter mile away. My wildland firefighting crew, the Truckee Hotshots, dropped the hoses we were holding, grabbed our chain saws and hand tools, and raced over on foot. The smoke was part of a pair of wildfires known as the North Complex, in California's northern Sierra Nevada mountains. It was early September 2020, just over halfway through fire season. A week later, the fire would kill sixteen people as it ripped through the Plumas National Forest. But at the moment, we still believed we could get ahead of it. Do you want to know the real Anthony Bourdain? Think before you answer. You and I and millions of others thought that when Anthony Bourdain lived, we knew how. We saw him living his life louder, bigger, more than we did, on his shows and speaking tours, read it in his books, absorbed it from his go-forth-and-fucking-do spirit. Then he died by suicide in 2018, and a hairline fracture formed between our Bourdain and this other, apparently life-disdaining Bourdain. Three years later, the documentary Roadrunner came out and revealed the ugly but very real end of Bourdain's life, and it jammed an icepick deep into that fissure. The man seemed to have day-dreamed about death as much as he'd lived his life. Now different books from two different people, both with the authority to discuss Bourdain's life, join Roadrunner in reconsidering the man by first tearing him down, then rebuilding him as a god. Like all mythology, they thump with the queasy, the uneasy, and an undercurrent of reality. Even as someone who writes about movies for a living, I have to admit that I was in no rush to return to a brick-and-mortar theater. It had been 18 months since I'd last seen a film on the big screen. But sometimes exceptions need to be made, which is how I found myself sitting down (rather nervously and double-masked) in the too-packed confines of Alice Tully Hall for the New York Film Festival's premiere of Dune. Within ten minutes, not only had I completely forgotten about the whole white-knuckle terror of being front-row at a potential super-spreader event; I was completely swept away by Denis Villeneuve's eye-candy vision, fully convinced that I was watching the best sci-fi movie of the decade. Yes, it's that good. So you're fired up about Dune hitting the big screen, and you're ready to dive into the world of Frank Herbert's beloved science fiction novels. Congratulations! You've got an exciting literary journey ahead of you. And whether you've dabbled in Dune lore before or you're completely new to the wild world of Arrakis, there's something for everyone to love in this titanic-sized series about power, violence, and fate.

|

Sunday, October 24, 2021

America’s Sperm Shortage and the Man Reaping the Benefits

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment